Anxiety Chapter from 'Empower your Kids'

You would not be alone if, when your child or teen tells you they feel anxious, you ask why. This is a natural reaction. We want to know why they feel anxious so that we can reassure them. The trouble with this is that it tends to make things worse because, instead of being present with the anxiety and managing it in ways I will explain in this chapter, they reject the feeling as ‘bad’ or ‘confusing’. They ask themselves ‘why’ and their brain says ‘I have no idea’ or ‘you are stupid to be anxious’ or ‘don’t you know, silly?’ In their desire to please you and also not to feel silly, they dig around for a logical or likely reason for feeling anxious and tell you that one. This may well be more understandable to you, the parent, and it will pacify the child for a while as distraction therapy, but it won’t show them how to self-soothe and manage the emotion themselves.

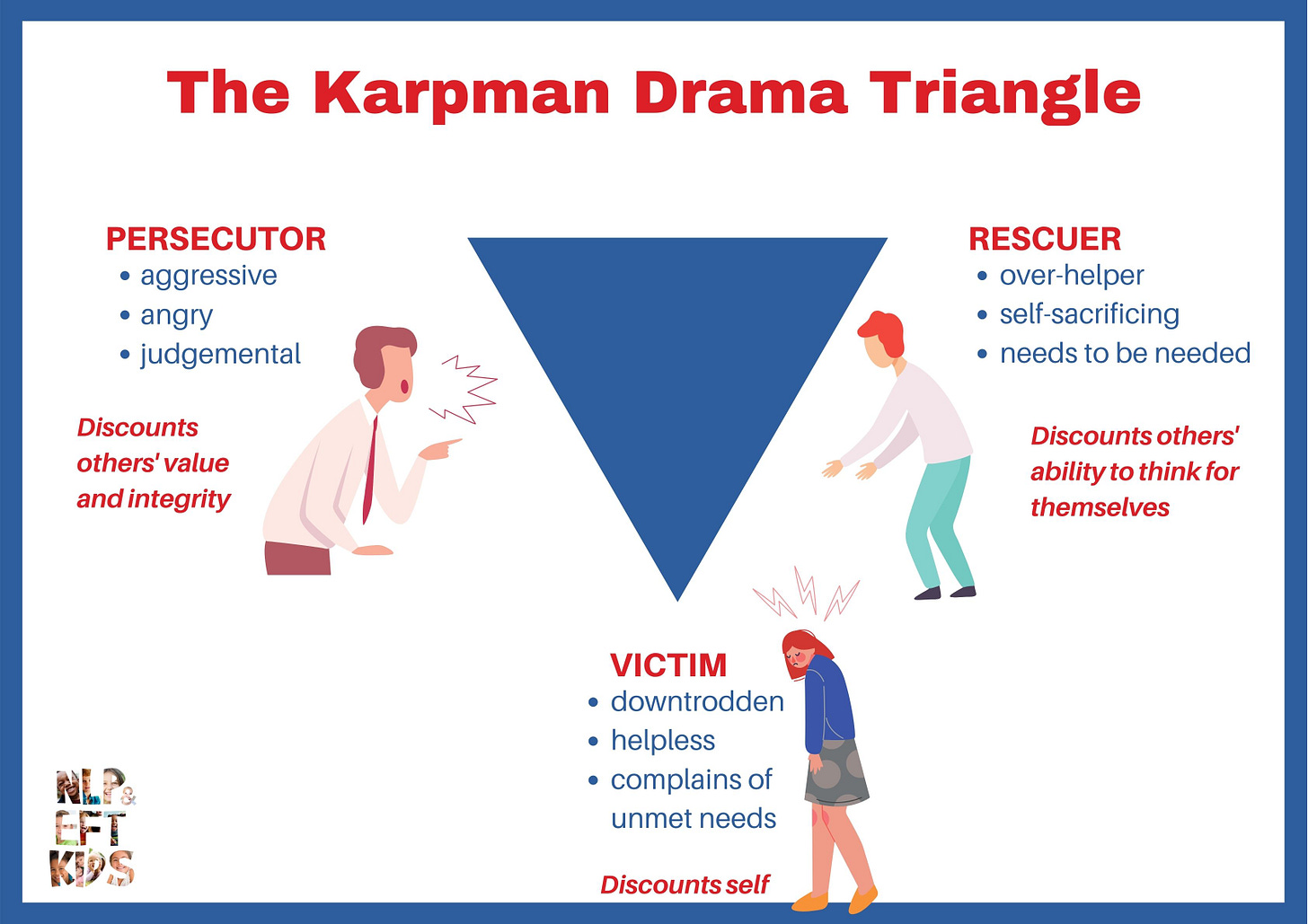

This results in a Drama Triangle where they become the victim who feels anxious and can’t do something, you become the rescuer who sorts everything out for them, and the ‘thing’ or person who was the supposed cause of the anxiety becomes the persecutor.

Of course, in the Fairy stories I mentioned earlier everything works out in the end as the victim gets what they want, but it is always as a result of it being ‘fixed’ by someone else.

Instead, you can help them with their anxiety by using coaching techniques to encourage them to perceive the situation differently.

Ask them what they could do, what their options are in this situation. They will be inclined to look at it from a binary point of view: do it or not do it. However, what if there were more options? Having more options opens things up. In order to think of options we need to use our imagination and to create possibilities. This already makes the situation look better.

Remember in Part 1 you read about the NLP Metaprogrammes and one of them was big chunk/small chunk, where I described how some of us are more comfortable with concepts and others need detail? Children who are faced with a chunk size that they struggle with will feel anxious. Show them how to chunk it down by asking what specifically they are concerned about and ask how they could find the smallest first step that they can manage. Show them how to chunk up by asking how, by doing this thing, they achieve something meaningful or meet some bigger purpose.

3. Have they done something similar before? Can they imagine being able to do it in the future? I like to use a Time Line for this exercise.

Exercise

Ask them to imagine a line along the floor. At one end is birth and the other end age 18yrs or when they leave school or university (choose an age that they will consider relevant). They should then stand on the point on the line which they feel represents today or their age now.

What do they want to do? Ask them to express it as what they want, not what they don’t want. When children are anxious they tend to drop into an ‘away from’ thinking pattern (metaprogrammes section in Part 1) and focus on what they don’t want. As you can imagine, whatever you focus on is what you get more of, it’s what you attract. So expressing it as an “I want ..............” is already a step in the right direction.

Now ask them to look back down the Time Line to their younger years and ask when they did something similar. Tempting though it might be to prompt them, as I’m sure you can think of just the thing, resist for as long as possible then just suggest rather than tell them. After all, to them it might not have been similar. The prompt might help them think of something that is.

They should go and stand on that point on the Time Line when they did that similar thing. If they absolutely can’t think of anything similar, they can go into the future on their line to a time when they can or will do this thing. Wherever they are standing now, whether at a point where they’ve done something similar or a time when they will do this, they are on a positive point representing possibility.

On that point, they can do an anchoring which is when you ask them to think of something that will remind them of being able to do this thing. Ask them to imagine that state of being how they want to feel. I’m reluctant to name it because it’s important you use their words. The opposite of anxious isn’t obvious. I’ve heard children use words like ‘confident’ or ‘brave’ rather than ‘relaxed’ or ‘calm’. Other words like ‘cool’ come up as well. What we don’t want is for them to say ‘not anxious’ as their desired state as this is what we call ‘away from’ thinking. It is notoriously difficult to anchor a state of not being something. So, encourage them to think about the feeling they do want not what they don’t want or want less of.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Understanding children and teens by Judy Bartkowiak to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.